Is Being Able To Roll Your Tongue Dominant Or Recessive? Here’s What’s True

Have you ever looked at someone and wondered if they could do that cool tongue-rolling thing? It’s a little party trick that some people have, and others… well, they just can't. It’s like a secret handshake for your mouth! You might have even tried it yourself in the mirror, wiggling your tongue this way and that, hoping for a magical curl. And then, the big question pops into your head: Is being able to roll your tongue dominant or recessive? It sounds like a science mystery, doesn't it?

For ages, people have been fascinated by this simple genetic trait. Think about it. It’s something you can see, something you can try, and it seems to run in families. Your mom might be a champion tongue roller, and suddenly, you realize your brother can do it too! Or maybe your dad can’t roll his tongue, and neither can you. It’s like a genetic puzzle piece that fits together, or sometimes, it just doesn’t.

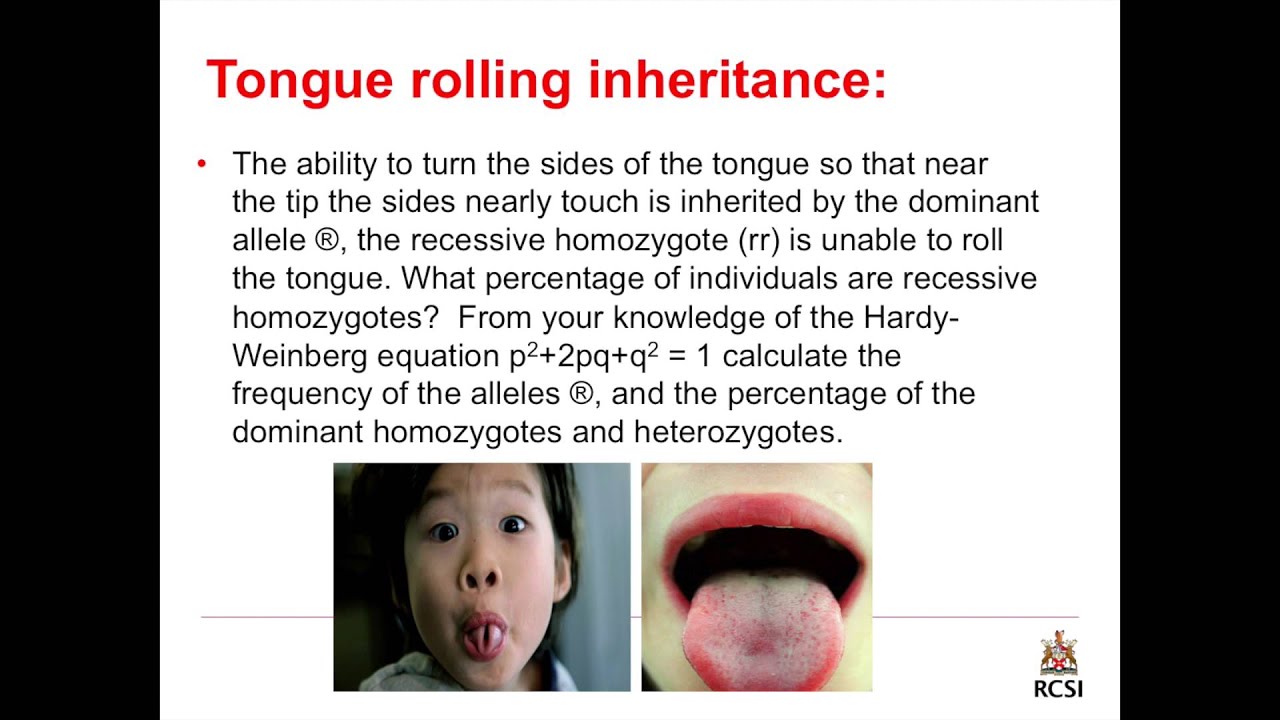

The idea of dominant and recessive genes is pretty neat. Imagine your genes are like little instruction manuals for your body. Some instructions are really loud and bossy – they’re the dominant ones. If you get just one copy of a dominant instruction, that’s what your body will do. Other instructions are quieter, more shy – they’re the recessive ones. You need to get two copies of a recessive instruction for that trait to show up.

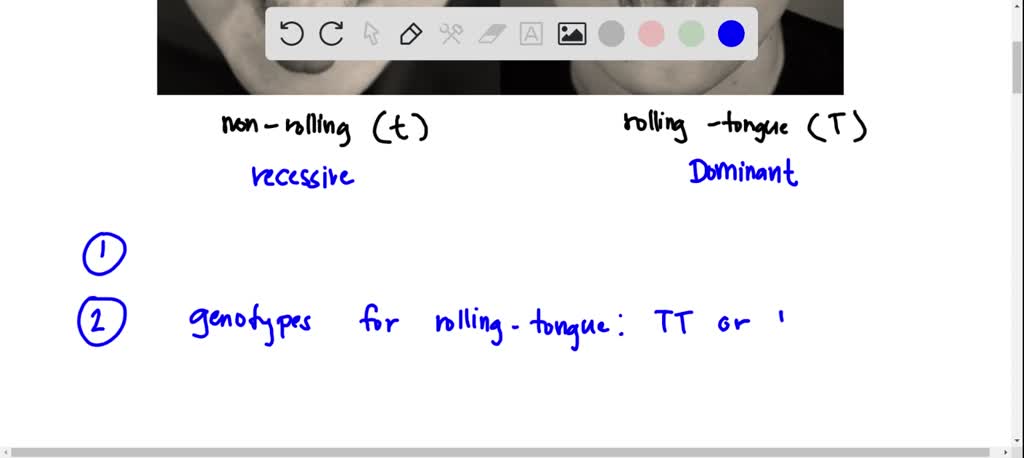

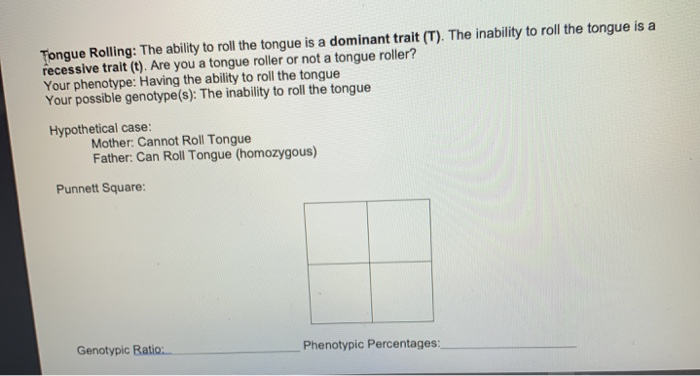

So, back to the tongue rolling. For a long time, the popular belief was that tongue rolling was a classic example of a simple dominant trait. The idea was that if you had even one "tongue rolling gene," you'd be able to do it. If you didn't have any of those "tongue rolling genes," then you wouldn't be able to roll your tongue. Simple, right? It was taught in schools, it was talked about at dinner tables, and it seemed to make sense for most families.

But here’s where things get a little more interesting. Science is always learning and refining, and it turns out that the story of tongue rolling might be a bit more complicated than a simple "dominant vs. recessive" tale. While it's still commonly presented that way, new research and observations have suggested that it might not be as straightforward as we once thought.

Some studies have looked at families where parents who couldn't roll their tongues had children who could. This is where the simple dominant/recessive model starts to get a little wobbly. If tongue rolling was purely dominant, then two non-rollers (who would only have the recessive gene) shouldn't be able to produce a roller. It’s like trying to make a red paint by mixing two yellow paints – it just doesn't work in that simple way.

This has led some scientists to believe that tongue rolling might be influenced by multiple genes, not just one. This is called polygenic inheritance. It's like having a whole committee of genes deciding whether or not you can roll your tongue, rather than just one lone wolf making the decision. When multiple genes are involved, the outcome can be much less predictable and follow more complex patterns than a simple dominant/recessive rule.

So, what does this mean for you and your tongue-rolling abilities? Well, it’s still a fun topic to explore! If you can roll your tongue, you’re part of a club that, according to the old rules, would have at least one dominant gene. If you can’t, you might have two of the recessive genes.

But the exciting part is knowing that the science behind it might be more intricate. It’s a reminder that even the simplest things, like how you curl your tongue, can have surprisingly complex biological explanations. It’s this sense of ongoing discovery that makes genetics so captivating. We think we have the answer, and then a new piece of the puzzle emerges, making us look again with fresh eyes.

Think about how many traits are passed down. Eye color, hair color, even whether you can taste certain things – they all have genetic components. Some are pretty clear-cut, like the classic examples of dominant and recessive traits you might learn about. But others, like tongue rolling, have started to reveal their more nuanced stories over time.

It’s this little mystery that makes the tongue-rolling trait so entertaining. It’s a conversation starter, a fun experiment to do with friends and family, and a window into the fascinating world of genetics. So, next time you see someone effortlessly curl their tongue, or you try it yourself, remember that you’re not just witnessing a party trick. You’re looking at a beautiful, and sometimes surprisingly complex, example of how our genes work. It’s a tiny, everyday marvel that makes you wonder what other secrets your DNA might hold!