What Caused The Great Depression In Europe

Picture this: it’s the roaring 1920s. Flappers are dancing the Charleston, jazz is king, and across the Atlantic, America is booming. Think of it like a really good party, everyone’s having a blast, the champagne’s flowing, and nobody’s really checking their bank account. Now, imagine that party suddenly gets a rude interruption. Someone flips the lights off, the music grinds to a halt, and everyone’s left standing in the dark, a little confused and very much broke. That, in a nutshell, is sort of what happened. Except, instead of just one party getting shut down, a whole continent was suddenly staring at empty pockets. So, what exactly was the cause of this massive, continent-wide party pooper, this thing we call the Great Depression in Europe?

It’s a question that’s been debated by economists and historians for, well, ages. And like most big historical events, it wasn’t just one thing. It was a messy, tangled web of problems, a perfect storm if you will, brewing for years. You know how sometimes one small decision can snowball into a huge mess? This was like a hundred small decisions, all colliding at once. And the echo of that crash? It reverberated for a very, very long time.

The Ghost of the Great War

So, let’s rewind a bit. Before the jazzy 20s, there was this little unpleasantness called World War I. You know, the one that was supposed to be “the war to end all wars”? Yeah, spoiler alert: it didn’t. And the impact of that war was like a massive, lingering hangover for Europe. Think about it – shattered economies, massive debts, and a whole continent trying to rebuild itself from scratch. It was a bit like trying to put together a giant, intricate jigsaw puzzle after someone’s spilled coffee all over it. Some pieces are missing, others are bent, and it’s just… hard.

One of the biggest lingering problems was reparations. Germany, after losing the war, was saddled with these enormous payments to the Allied powers. It was a staggering amount of money, and honestly, it was a recipe for disaster. How could a defeated nation, already struggling to get back on its feet, possibly afford to pay that much? It was like asking someone who just lost their job to pay off your mortgage. Not exactly a sustainable plan, right?

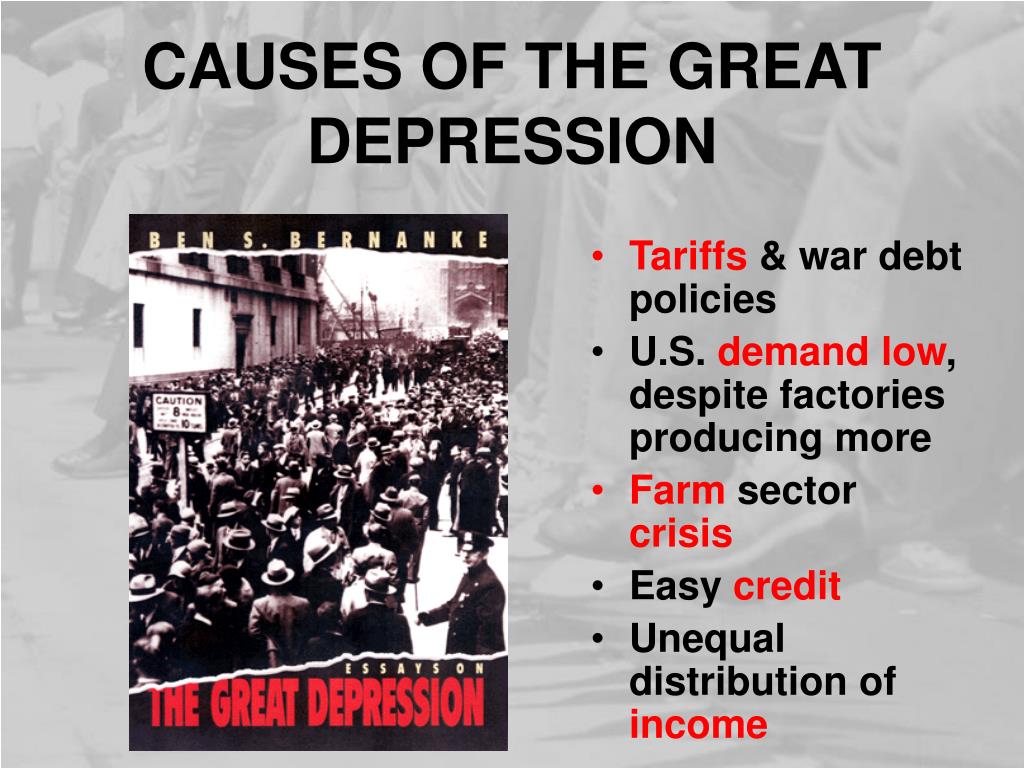

This reparation burden wasn't just a German problem, though. It created a chain reaction. France and Belgium, who were owed these reparations, relied on that money to rebuild their own countries and pay off their own war debts, many of which were owed to the United States. So, if Germany couldn't pay, France and Belgium couldn't pay, and then the whole system started to creak and groan. It was a bit like a game of Jenga, with each block representing a nation’s financial stability.

America’s Money Machine (and its Sudden Stop)

Now, here's where the party analogy really kicks in. After WWI, America was in a fantastic position. It hadn’t been directly ravaged by the fighting, and it had become a major creditor. Basically, everyone owed America money. And America, being in its booming 20s phase, was happy to lend more money to Europe, especially Germany, so they could, you know, try to pay off their debts. It sounds a bit convoluted, doesn't it? Like a financial ouroboros, eating its own tail.

This cycle of American loans, German reparations, and then payments to Allied countries (and eventually back to America) was like the lifeblood of the European economy. It kept things chugging along. But this system was incredibly fragile. It depended heavily on the continued willingness and ability of the US to lend money. And what happens when the lender suddenly decides to call it a day? You guessed it – everything grinds to a halt.

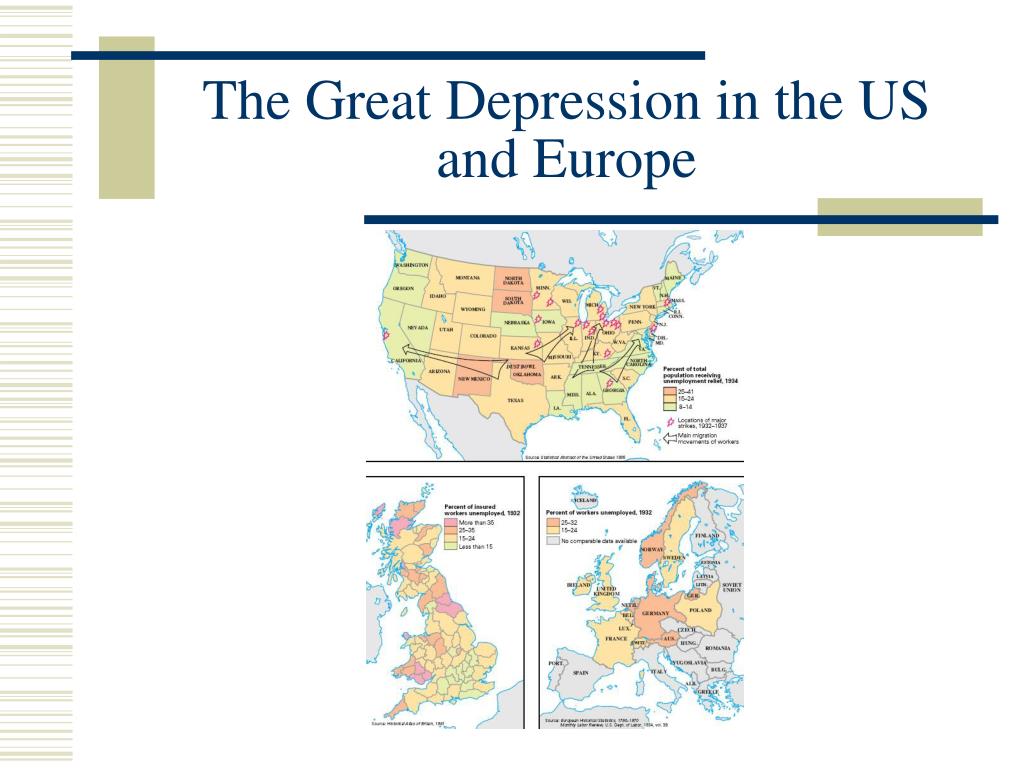

This brings us to the infamous Wall Street Crash of 1929. Now, the crash itself happened in America, but its impact was felt globally, and especially in Europe. Think of it as the big, dramatic mic drop that silenced the entire party. Suddenly, American investors, who had been pouring money into Europe, were scrambling to pull their cash back home to cover their own losses. This withdrawal of capital was like yanking the plug out of the European economic machine. It was devastating. Loans dried up overnight, businesses couldn’t get credit, and the whole financial system started to seize up.

More Than Just the Crash: Economic Weaknesses

While the Wall Street Crash was the dramatic trigger, the European economies were already wobbly. They weren't exactly built on solid bedrock, you know? There were underlying issues that made them particularly vulnerable. One of these was the over-reliance on certain industries. Many European countries had become very specialized, focusing heavily on manufacturing, for instance. But what happens when demand for those goods suddenly plummets? You’re left with factories sitting idle and workers with no jobs. It’s a classic case of putting all your eggs in one basket, and then dropping the basket.

Another significant factor was protectionism. This is a fancy term for countries putting up barriers to trade, like imposing tariffs (taxes on imported goods). In the 1920s and early 1930s, many countries started doing this. They thought, "Hey, let’s protect our own industries by making foreign goods more expensive." Sounds logical, right? But in practice, it backfired spectacularly. When one country puts up tariffs, other countries usually retaliate, and suddenly, international trade grinds to a halt. This meant that even if a country could produce goods, it was harder to sell them abroad, and harder to import necessary raw materials. It was like everyone deciding to close their doors and windows, and then wondering why no one was visiting.

The interconnectedness of the global economy, which we sometimes celebrate as a good thing (yay, globalization!), became a massive liability during this crisis. When one part of the system breaks, the damage spreads like a bad cold through a crowded office. The collapse of trade meant that even countries not directly involved in the financial crash were severely impacted.

The Gold Standard: A Golden Straitjacket?

Now, let’s talk about something called the Gold Standard. This was a monetary system where a country's currency was directly linked to a specific amount of gold. It was supposed to provide stability, a kind of universal yardstick for value. But during the Depression, it became more like a golden straitjacket. Because currencies were pegged to gold, countries couldn’t just print more money to stimulate their economies. They were limited by their gold reserves.

This meant that when the economic crisis hit, countries were often unable to devalue their currency or inject liquidity into their banking systems. They were essentially trapped by their gold. Imagine being in a sinking boat and having a valuable but heavy chest of gold. You can't throw it overboard to lighten the load because it's too precious, but it’s also dragging you down faster. Many economists argue that clinging to the Gold Standard prevented governments from taking the necessary measures to combat the Depression effectively.

When the crisis deepened, and countries started abandoning the Gold Standard one by one, it caused further instability and uncertainty. It was like everyone in a game of musical chairs suddenly realizing there weren't enough chairs, and then scrambling to find one, knocking others over in the process.

Government Policies (or Lack Thereof)

And then there were the government policies. Or, in some cases, the lack of effective policies. Initially, many governments were hesitant to intervene too heavily in the economy. The prevailing economic thought at the time was that economies would naturally self-correct. This idea of laissez-faire economics, which basically means "let it be," proved to be disastrously wrong in the face of such a severe crisis. It was like telling a patient with a broken leg to "just walk it off."

When governments did finally start to act, their responses were often too little, too late, or simply misguided. Austerity measures, where governments cut spending to balance their budgets, often made things worse by reducing demand and increasing unemployment. It was like trying to save money on fuel while your car is running out of gas – you’re just making the problem worse.

The political landscape in Europe also played a role. Many countries were still grappling with the aftermath of WWI, facing political instability and social unrest. This made it harder to implement bold, coordinated economic policies. The rise of extremist political movements, partly fueled by economic hardship, further complicated matters. It’s a vicious cycle, isn’t it? Economic hardship breeds political instability, which in turn hinders economic recovery.

The Domino Effect

So, to recap, we had a continent still reeling from a devastating war, burdened by crippling reparations. Then came the American financial boom, which temporarily masked these issues, but was built on a shaky foundation. When America’s party ended with the 1929 crash, it pulled the rug out from under Europe. Add to this protectionist trade policies, the rigidities of the Gold Standard, and often ineffective government responses, and you have a recipe for a truly epic economic collapse.

It wasn’t just one single cause, but a confluence of factors, a perfect storm of economic, political, and financial woes. The Great Depression in Europe was a stark reminder that economies are complex, interconnected systems, and a shock in one area can have ripple effects far and wide. It was a hard lesson, learned at a very high cost, and one that shaped economic thinking and international relations for decades to come. It’s the kind of event that makes you pause and think, "Wow, how did we even get here?" And the answer, as we’ve seen, is a bit of a doozy.