Which Of The Following Necessarily Occurs During An Economic Recession: Complete Guide & Key Details

Remember that feeling? You know, when suddenly your favorite local coffee shop, the one where they knew your order by heart, has a "Closed Indefinitely" sign taped to the door? Or maybe your uncle, who's always been the life of the party and worked in construction, starts looking a little more… worried than usual. That quiet shift, that subtle tightening in the air, that's often the whisper of an economic recession creeping in. It's not always a dramatic crash (though it can feel like it!), but it's a definite change in the economic winds.

I remember one time, a few years back, my neighbor, Sarah, a super talented graphic designer who freelanced for a bunch of startups, was suddenly complaining about how hard it was to find new clients. "It's like everyone just slammed the brakes on new projects," she'd say, with a slightly panicked edge to her voice. Within a few months, a couple of her bigger clients had either folded or drastically cut their budgets. That's the kind of ripple effect we're talking about. It's not just the big, scary numbers on the news; it's the tangible impact on the people and businesses around us.

So, when we hear that dreaded word, "recession," and then someone asks, "Okay, but which of these necessarily happens?", it's a fair question, right? It feels like a lot of things could happen, but what are the absolute, no-ifs-ands-or-buts, this-is-the-definition kind of events? Let's dive into what actually goes down, and maybe clear up some of the confusion. Because honestly, it's easy to get lost in the jargon and the doom-and-gloom headlines.

The Big Question: What Necessarily Happens?

This is where we get to the nitty-gritty. When economists talk about a recession, they're not just saying "things are a bit slow." There are some pretty specific criteria that need to be met. Think of it like diagnosing a patient – you need a certain set of symptoms to confirm the illness.

The most widely accepted definition, and the one you'll hear tossed around most often, involves a significant decline in economic activity spread across the economy, lasting more than a few months, normally visible in real GDP, real income, employment, industrial production, and wholesale-retail sales.

Whoa, that's a mouthful, isn't it? Let's break it down because it's crucial. This isn't just about one sector struggling; it's a widespread, sustained downturn.

The Gold Standard: Two Consecutive Quarters of Negative GDP Growth

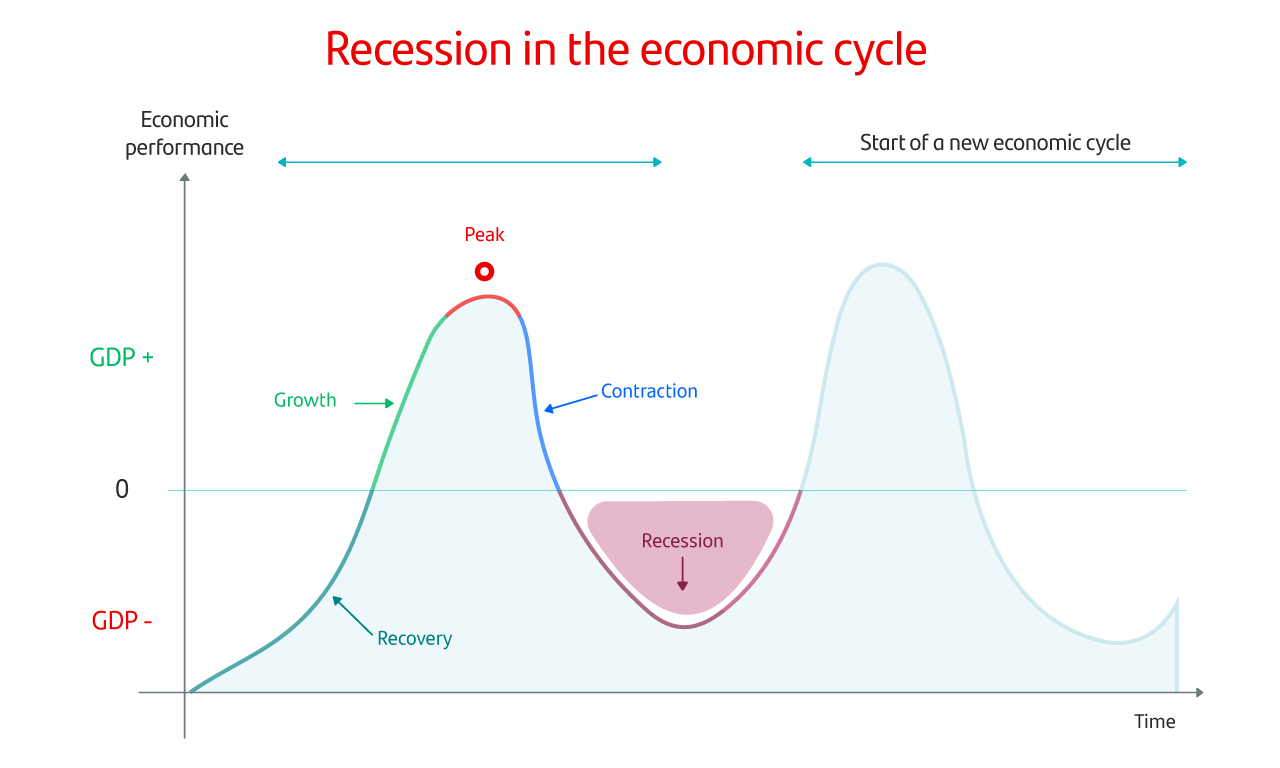

Okay, this is the big one. The most commonly cited indicator, the one that gets plastered on every economic news site, is the idea of two consecutive quarters of declining real Gross Domestic Product (GDP). What's GDP, you ask? Think of it as the total value of all the goods and services produced in a country over a specific period. It's like the ultimate scorecard for an economy.

So, if the country produces less stuff and provides fewer services in the first three months of the year compared to the last three months of the previous year, that's a decline. And if it happens again in the next three months, boom, that's the technical signal for a recession. It's a simple, albeit somewhat backward-looking, way to measure if the economy is shrinking.

Now, why "real" GDP? Because nominal GDP can go up just because prices are rising (inflation!). We want to see if the actual amount of stuff being produced is going down, not just its dollar value. So, they strip out the inflation effect. Pretty smart, right?

However, here's a little insider secret: While this two-quarter rule is super common and easy to understand, the official arbiter of recessions in the United States is the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER). They're the ones who actually declare when a recession starts and ends.

And the NBER? They don't just look at GDP. They take a broader view. They'll tell you they look at a range of indicators, and they're not bound by that strict two-quarter rule. They're looking for that significant decline in activity spread across the economy. So, while two quarters of negative GDP is a strong clue, it's not the only thing they consider, and sometimes they might call a recession even if GDP hasn't technically dipped for two full quarters, or conversely, might wait longer if other indicators are mixed.

So, to directly answer the question: Does GDP necessarily fall for two consecutive quarters? Not necessarily in the absolute, rigid, NBER-definition sense, but it's the most common and widely accepted signal. If you see that happening, you can be pretty darn sure a recession is either underway or imminent.

Beyond GDP: The Other "Necessarily" Occurring Factors

While the GDP is the headline grabber, the NBER's broader definition tells us there are other things that have to be happening, to varying degrees, for it to be a true recession. These are the supporting cast members to the GDP star.

Declining Employment: The Painful Reality

This is arguably the most felt aspect of a recession for most people. When the economy contracts, businesses often see a drop in demand. What do they do when they're not selling as much? They start cutting costs. And one of the biggest costs for any business is its workforce.

So, yes, a significant increase in unemployment and a decline in employment is a virtually guaranteed feature of a recession. This means more people are losing their jobs, and it becomes harder for those looking for work to find it. The unemployment rate ticks up, and the number of jobs available shrinks. It’s not just a few isolated layoffs; it’s a trend across many sectors.

Think about it: if companies are producing less (lower GDP), they don't need as many hands on deck. It’s a direct cause-and-effect. This is one of those things that, while maybe not the official starting gun like GDP, is an almost inevitable consequence that makes a recession real for everyday folks. It’s hard to argue that an economy is doing well when people are struggling to find or keep their jobs.

Slumping Sales: Less Buying, Less Selling

If people are losing jobs or worrying about losing their jobs, what happens to their spending? They tighten their belts. They cut back on non-essential purchases. This leads to a noticeable decline in consumer spending and retail sales. Suddenly, that new gadget you wanted, or that fancy vacation, might get put on the back burner. Businesses that rely on people buying things see their sales drop.

Similarly, wholesale sales will also likely fall. If retailers aren't selling as much, they won't be ordering as much from wholesalers, who in turn won't be ordering as much from manufacturers. It’s a cascading effect that spreads throughout the supply chain. This decline in the movement of goods and services is a strong indicator that the economy is slowing down significantly.

This isn't just about "things slowing down a bit." It's a broad-based reduction in the volume of transactions happening in the economy. It signals a lack of demand and a general cautiousness among consumers and businesses alike.

Reduced Industrial Production: Factories Slowing Down

This ties in directly with falling sales and GDP. If demand for goods is decreasing, factories don't need to churn out as much. So, industrial production, which measures the output of factories, mines, and utilities, typically experiences a significant drop during a recession. This means less raw material being processed, fewer goods being manufactured, and a general slowdown in the industrial sector.

When factories start producing less, it has knock-on effects. They might need less energy, fewer raw materials, and yes, fewer workers. It’s another piece of evidence that the economic engine is sputtering.

Shrinking Real Income: Less Money in Pockets

This is the flip side of declining employment and reduced economic activity. When businesses are struggling, they often can't afford to give raises, and sometimes they even have to cut wages. Combined with job losses, this leads to a general decline in real income for households. People have less money coming in, both from wages and potentially from investments. This further dampens consumer spending, creating a vicious cycle.

It’s not just about nominal income (the number on your paycheck); it’s about real income, meaning what that money can actually buy after accounting for inflation. So, even if your paycheck stays the same, if prices go up, your real income has effectively decreased.

What Doesn't Necessarily Happen? (Common Misconceptions)

Now that we've established what does tend to happen, let's talk about what people think happens but isn't a guaranteed sign of a recession. It’s easy to conflate a recession with other economic woes.

Stock Market Crashes? Not Necessarily the Defining Factor.

Everyone’s eyes go to the stock market when things get bumpy. And yes, the stock market often declines during a recession. Why? Because company profits are expected to fall, and investors become more risk-averse. However, the stock market can have significant downturns without it being a full-blown recession. Think of a sharp correction or a bear market that doesn't drag the broader economy down with it.

The stock market is a forward-looking indicator and can be very volatile. While it often moves in the same direction as the economy, it's not the definition of a recession. The NBER doesn't use stock market performance as a primary indicator for declaring a recession.

Hyperinflation? Nope, Usually the Opposite.

This is a big one. Recessions are generally associated with deflationary pressures or at least very low inflation, not hyperinflation. When demand falls, businesses often have to lower prices to sell their goods. So, instead of prices skyrocketing, you might see them stagnate or even fall. Hyperinflation is a runaway price increase, a sign of a completely different kind of economic crisis.

So, if you hear someone talking about a recession causing rampant inflation, that's usually a misunderstanding. Inflation can occur for many reasons, but it's not a necessary consequence of a recession; in fact, the opposite is often true.

Business Bankruptcies Across the Board? Not Always.

While bankruptcies will likely increase during a recession, it's not a certainty that all or even most businesses will go under. Some businesses are more resilient, especially those that provide essential goods or services. Stronger companies might even weather the storm or even acquire weaker competitors.

The key is that the decline is widespread. Not every single business will cease to exist. However, the rate of bankruptcies and the number of struggling businesses will certainly increase.

A Complete Collapse of the Financial System? Thankfully, Not Necessarily.

This is a scary thought, and it can happen in severe recessions (like the 2008 financial crisis), but a "complete collapse" isn't a defining characteristic of every recession. Recessions can range in severity. While financial systems can come under strain, and banks might face difficulties, it doesn't automatically mean the entire system implodes. Governments and central banks often step in to prevent such catastrophic outcomes.

The "Vicious Cycle" of Recession

It's important to remember that these factors are often interconnected, creating what economists call a "vicious cycle." Declining consumer spending leads to lower business revenue, which leads to layoffs, which further reduces consumer spending. It’s like a snowball rolling downhill, gaining momentum.

Understanding these key indicators helps us move beyond the fear-mongering and the generalized panic that often accompanies discussions about economic downturns. It’s about recognizing the patterns and understanding the fundamental shifts that define a recession.

So, the next time you hear the R-word, you'll have a clearer picture of what's actually going on, not just what people are saying might happen. It’s about informed awareness, not just anxious anticipation. And in the often-turbulent world of economics, a little clarity can go a long way.